Peterhead, Scotland, July 2011. Ex-submariner Dave Rogers arrived on the bus from Aberdeen to join Dr Chris Huby, a retired Edinburgh doctor, and his Norwegian wife Guro,

By Guro Huby

in an attempt to deliver La Lucha to Bergen.

It began with a decision to move from Edinburgh back to my native Norway after 30 years in Britain. My husband Chris had bought La Lucha two years earlier and we had grown rather fond of her. She was designed for the choppy and shallow waters of the East Anglian coast and built for performance rather than living space. She might be lacking in comfort, but people who know about these things kept telling us that she sails beautifully. But then, tootling around the Firth of Forth hardly provides a realistic test. A common reaction to our proud announcement that we intended to cross the North Sea in a 28-footer was a sharp intake of breath: "Wooah! Gutsy!" Gutsy? Or foolhardy? But our pride prevented us from loading her on a lorry or having her delivered by a professional skipper. We also thought that by sailing to our new life in Norway we were properly marking the transition in our lives.

We learned three lessons, all the hard way. First: sailing is a collective enterprise where time on the water consists of barely one hour in every five, with only a part of that precious time being spent under sail. Second: voyages under sail are never linear movements from A (Granton on the Firth of Forth) to B (Bergen in Norway). You have to be ready for the unexpected. Third: Our La Lucha turned out to be a gem of a seagoing boat.

By way of the first lesson, Chris started preparing the yacht early in the year. He installed new VHF radio, depth sounder and Tacktick micro compass. He renewed the jackstays and the liferaft and checked the engine and electrics, spending sleepless nights worrying about raising the storm jib. We learned that asking for advice from five experienced sailors produces at least seven, usually conflicting, answers.

He took our rather old sails to be valeted. Laughter erupted when we told them we intended to use these sails to cross the North Sea. We ordered new sails and while we were at it we decided to get lazyjacks and a stack. The sails were promised for beginning of June. They arrived mid-June and the jib was too big, because we made the wrong measurements.

In April came the collective boat yard job of craning wintered boats from the hard at Granton. It coincided with the most fraught period of our house move. On launch day, La Lucha suffered a serious leak. Tempers frayed as the option of lifting her out of the water again was considered. One of the can-do men at the boat club suggested taking her up on the slipway and said that the leak could be fixed. He telephoned his wife to let her know he would not be home for tea. The leak was in an area of softened wood around the sacrificial anode. The boat club man prepared an epoxy repair on the outside. Chris worked on the inside in confined spaces. He stuck his foot in the engine and dislodged the newly mounted fuel filter. But the seal worked and La Lucha turns out to be dry as a bone. Touch wood! Our saviour only wanted a bottle of gin for his trouble. We gave him two.

If craning is stressful, what about the annual ordeal of stepping the mast? We have never, on our own, tackled the tangles of halyards, forestays, mainstays and backstays when the mast is on the ground. Trying to envisage which bit will need to go where for an upright mast was beyond us, and a spaghetti knot was being lowered on to the deck to be fitted and secured in twenty minutes before the boat got stuck in the mud of low tide. We felt bad knowing that we were creating unnecessary work for another boatyard friend who was helping us. We felt clumsy and inadequate, depending on others to pursue our Norway adventure. But we had also come to realise that achievement in the boat yard or at sea depends on ties of service and obligation among many people with different skills and contribution. For now we can only supply the experienced with gin and appreciate their superior knowledge. One day we hope to be able to give back something more useful. By mid-May we had still not yet sailed her, let alone put to sea. At this stage we would have accepted ten pounds from anyone offering to buy La Lucha. Wrong. We would have paid a hundred pounds to anyone willing to take her off our hands. The crossing was off. We might do it next year. I was fed up doing all the moving work on my own and Chris could not face another day on the boat tackling a list of jobs, which seemed to grow with each task accomplished.

But then we had our first sail of the season and La Lucha danced across a south westerly, force 3 to 4, on a broad reach. It does not take more. We were back on.

A book on cruising the Norwegian coast for foreign sailors assured us that crossing the North Sea poses few problems. The prevailing winds in the summer are west/south west and generally light. That description was far from our experience.

In 2011 and 2010 north easterly winds, often strong, were the rule. Several tentative departure dates came and went. Then on one clear, sunny and almost windless Sunday at 4 a.m. we chugged out of the Forth and set a 46 degree course towards our destination. Twelve hours later Chris discovered that the alternator was not working and the domestic battery was discharging, even with the engine running. We went into Peterhead, north of Aberdeen, to get it fixed, fully intending to set off again one day later.

Alas, we had lost our weather window and we did not get away. Returning from a trip to explore the Moray coast we discovered that the repair to our alternator had not solved the problem and our domestic battery was flat again. Our friends had run out of time and had to go home. Without power to run navigation instruments, without the necessary experience and sailing skills for the prevailing conditions, we saw our North Sea adventure blow away on the strong north and east winds.

Sometimes a rescuer arrives when things look most bleak. Our rescuer was Andrew Rosthorn, who had brokered the sale of La Lucha two years earlier and had road-hauled her from the River Ribble to Edinburgh. By an incredible stroke of luck we spotted a lorry in Peterhead carrying the name of Sealand Boat Deliveries, Andrew's firm. Chris spoke to the driver, Mark Chapman, who was sure that Andrew could arrange help. Mark needed some help to move a yacht for craning to his lorry for transport to Ireland. So we helped him with his boat and Andrew made it his mission to find us a skipper for our boat. He rose to his reputation as a problem solver.

The grim prospect at Peterhead revealed a lorry from Sealand Boat Deliveries

We motored out of Peterhead harbour on Friday lunchtime in sunny weather with no wind. Dolphins followed us. But the calm was short lived. The wind gradually increased by evening, up to 25 knots with odd seas coming at us from two different directions. We ate our one meal of the passage with some difficulty. Our autopilot "Alfred" was deemed unable to helm, for fear of broaching, as indeed was I. I went to bed but was unable to sleep. The winds and waves persisted overnight and the next day, but they came beam on and Alfred was back on the job.

The weather forecast was wrong. We seemed to be getting Sunday's low a day early. Actually, we were getting low on a worsening low, but we did not know this yet. At the end of my afternoon watch on the second day the seas flattened and the wind abated. We drew a sigh of relief. Dave planned to rest a bit after the battering, have a meal and give La Lucha a bit of a breather.

It was not to be. The wind got up again and the seas got rougher. La Lucha coped pretty well fully reefed, but we were being thrown about by the combination of wind and waves. I succumbed to a splitting headache and then got sea sick, leaving Dave and Chris to do all the work. Not that I could have been much use in those conditions. I went to bed, with the boat shaking and rattling in the wind and waves. At one o'clock in the morning I awoke with a jolt and look out to see Dave thrown across the cockpit by a wave. He swore loudly and told me to wake Chris as we have to "lie ahull for a while".

I froze. Lying ahull is a measure of last resort in the instructions for rough weather sailing I have read. On the sea survival course I attended, the message was to keep going. However, the strength of the wind and waves separately was not the main problem, although it was gusting 35 at times. The danger was from the winds coming at us from the east, and the waves from the south, creating troughs that might have turned us over. Dave made a sea anchor out of an old jib and put out a "Sécurité, sécurité, sécurité" message to say what we were doing. Nobody seemed to notice or to bother. We were within a few miles of an oil platform, but drifting away from them.

That night and for the second time in three months there was a classic East Anglian sloop going very cheaply. This time however, she was offered as a proven seaworthy vessel. We realised how strong she is, ploughing faithfully through these rough seas. She shook, rattled and clattered (the clatters improved when I was well enough to wash and put away the coffee cups and pot in the sink) and occasionally groaned a bit, but not once did she give cause for concern. She may not be that big, but she certainly is perfectly formed. And once she stopped fighting the waves, things calmed down and we went to sleep for a few hours. Chris woke up first early on Sunday morning to see with some shock that the wind has shifted through the night. We had drifted to within about a mile of the oil platform and were getting closer. Dave and Chris scrambled on deck and got us away from there with impressive speed. The oil platform sent a RIB to find out how we were. They did not specify whether mentally or physically. If they were impressed by our presence aboard a small yacht in these seas, they did not show it. There was however no hiding their astonishment.

The weather calmed down during Sunday, and by mid afternoon conditions were easier, with all three of us sitting in the cockpit chatting. I managed to hold down a cup of tea. Alfred had bitten the dust in the storm and we had to helm, which added to the magic of our anticipated approach to the Norwegian coast. By evening there was a 15kt SW wind with clear skies, a full moon and only a partially-set sun. It was just what we had hoped for. Chris helmed until dawn, when we could just make out Norway against the brightening sky and waves. At one point a cruise ship came quite close so that the passengers could take pictures.

Bergen ahead

Guro Huby on Sognesjøen

Dr Chris Huby on Naeroyfjord

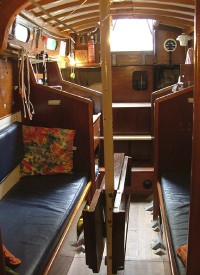

CLICK this picture of La Lucha's saloon for yacht transport news from 2009.

NAVIGARE NECESSE EST, VIVERE NON EST NECESSE

To sail is necessary, to survive is not necessary.

Attributed by Plutarch to Gnaeus Pompeius who sent sailors to sea in bad weather to bring grain from Africa to Rome.

Ici on trouve la metéo, des vendeurs de bateaux, les spécialistes du transport bateau et la cyberbourse électronique des transporteurs.

Ein Amerikaner aus Kalifornien war 1997 unser erster Kunde. Er liess seine Yacht in Amerika von Küste zu Küste transportieren. Seit diesem ungewöhnlichen Boottransport, hat unsere Transportbörse hunderte von Yachtbesitizern mit anderen Bootstransporteuren in Verbindung gebracht. Stellen auch sie ihr Transportproblem auf dem BTX board dar. Die Bootstranporteure geben kostenlos Ratschläge und bieten ihnen Preise an.

Luxury Boat Hire Norfolk Broads with richardsonsboatingholidays.co.uk

Sealand Boat Deliveries Limited

Operations Office,

Tockholes,

Darwen.

BB3 0NA

England

Telephone: 01254 705225 International +44 1254 705225

International fax : +44 1254 776582

e-mail address: ros@mcr1.poptel.org.uk 1078992 England

VAT Reg: GB 147 2903 64

Use the btx

questionnaire to give us the vital details of your boat transport projects on http://www.btx.co.uk/btxforms.htm